|

What is that? Above me, what is that? Inside me, what is that? What is that I see and touch, what is it I have known and found and remembered but cannot tell in words, preserve in words, make eternal in words. What is that I cannot save, from itself and from disease and from time, in words? What is that which I know and lost and see in dreams, as revelations, blind prophecies? What is that intelligence divine, as Boethius had it, and the mortal reason which stumbles and falters and falls about it? Why, us! — This, only this, I know. I lie seeing it. I lie next to it. I’ve faltered and fallen about it. I see it and know it but cannot take it, save it, preserve it, tell it — for eternity. This is the tragedy of language, this our damnation, this the mark of our sin — that we are fleeting, that the world must fall away, that we do not know what we see, that we stumble over our feet, that we make a terrible clatter with words that still must end in silence, nothingness, emptiness — that language and we are mortal — that we can only begin and not be, that we can only begin to exist and not exist, that we are mute — that we stumble and fall in heaps about an empty center, in laughable absurdity, in empty metaphor. — This is the mark of our sin. Where is our sin? Is it an emptiness or an excess? Can we see our sin or only its mark? We are damned to half-blindness; we only know marks and symbols, metaphors and vessels of our truth, allegories and abstractions of ourselves; we only know language and not the thing inside it, not the thing it holds. For what the war? What is there? What do they want? What do they have, what have they known that they have not (that is not there), what have they lost, what is that which they cannot lose, that for which the earth is washed in blood. I see them and where they go. I know the stolid stillness of defense. I know they are virtuous. For what the war? For them and for their wings I stand. For the sacred mind, for the mind’s freedom I lay down utterly my neck. For the mind is to be worshipped, for God is of the mind, for the mind made the world and then a God to make it. For a person is mind and not body. For the mind is the soul. I worship the mind and collect its tears. And its tears are words, its tears are language — and we are minds but do not know them, and that separation and that distance is the distance of man from God, of body from mind — we are minds but do not know them, we do not know ourselves — damned to only look ahead, damned to half-blindness — we do not know our minds, we do not know ourselves — and words (language) are our tears — ours is a language of weeping. Silence. For what the war? God and his word are the mind’s, that divinity’s, that humanity’s. The mind thought, and all came to pass. The mind made God. Poetry as possession of the poet. As Heidegger has it, poetry comes from beneath the poet, from the earth, through the poet; poetry as the earth’s mire and filth, poetry as disgust at the earth and at nature. — Poeta vates. The poet as prophet. Chaucer’s mundanity, Chaucer that pierced the folds of history, that rose from medieval tedium and made himself naked to the night storm, to the violence of the future. Geoffrey Chaucer, that remembered the pining Boethius and the self-pricking Augustine and the free-living ancients, that wound history and tradition and poetry into a vortex that unfurled itself two centuries later, and the Renaissance and Shakespeare and Milton and brave England came to be. And Geoffrey Hill that poetic digger who died seven years ago, who saw and birthed our human past into the back-blind present and put on us metaphor’s armor that we may stand and hold and live past the night storm. I found that armor and wore it and it has heavied me and made me see the earth beneath me, Heidegger’s earth beneath the world, Heidegger’s poetry, Heidegger’s poetry as the brute earth and sea that possess me and rise through me, through my head as an Athena from her depraved father. — The poet is blind and is nothingness, is absence, and poetry is of itself, conceals itself, looks forward and back, is presence, is everything. — Chaucer that first wound up the mystery. Baudelaire’s dreams, Baudelaire’s abyss, abyss of thought and symbol. The abyss of language. Language that is at once overcome by poetry, conquered by poetry, and that births poetry, lays it down, structures it, births it. Baudelaire’s dreams: the sea, the winged poet and the mocking sailors, the morning’s muses and the night storms, phantasms, the night’s fever, the disease of thought. Baudelaire’s dream of a literature after God, a world after God, a people that killed God — as Hegel and Nietzsche dreamed not long or far away. This dream Bach in his blind cave knew, Bach new God had died, and so sought to make God with his cantatas, his passions, his fever and fugue, the Art of the Fugue, Die Kunst Der Fugue. But hypocrisy can be smelt. He was frightened, and I forgive him. Baudelaire’s dreams, Baudelaire’s abyss. My disgust at myself, my disgust at death, my life as a turning inwards and disgust at the sight. Death can be smelt. Schumann smelt his death, and they thought him mad. Van Gogh too, Keats too, Shelley and Byron perhaps. Yes, Death can be smelt.-- The mind is the only eternity. The mind is the only God. And I lay it down, mind, eternity, God, in ink onto the page. How many eternities will I make? Many, many. And I will need none of them between the last breath and death, that silence, that dark metaphor, that abstraction of the flesh, — I’ll need none of them. But see, death is no eternity; it is a cursed and fallen soul. It is all except eternity. It is the maker of eternity. Only my words, only my tears, will be left when it comes and takes me — Death, the taking wind, my winter — And my words will sing in the winter of my days. These numbers, all this I have been given, I have found by prophecy under the first snow of winter — where the flowers were, where the earth lies dead, where the poet digs. The poem as a choice, as the necessity of itself over all else. The poem as the negation of eternity. The poem as a radical, political choice of itself over all else — a choice of the oblivion of language, the temporality of language, the inadequacy and vulgarity of language — a rejection of eternity for withering ecstasy — a rejection of eternity for oblivion, of divinity for damnation, of divinity for sin, of God for man. “In the day we eat thereof our doom is, we shall die.” So Milton heard, so the Fathers, so the twentieth century mutters and spits, so I remember, so we know and say, so we thank them that made us. Winter blows the taking wind. A fever comes. A cold fever. The body rots under new snow. Winter takes away. The wind takes away. Life takes away. Death takes away. And what is left? The word that is the mind. The mind that is the word. The mind that is God. God that is the word. The poet that is God. The mind, the word, the poet. Neither life rots me nor the wind blows me off, because my word remains. All this I found in winter, heard of the wandering wind. All this in winter, of the wind. Nickolas vaccaroNickolas is a columnist for the Paper Crane.

0 Comments

5/9/2023 Book Review: “Devilish” Meets Psychopathic, Soul-Sucking Transfer Students and Immortal BoyfriendsRead NowNotable for her witty writing, Maureen Johnson is best known for her upper middle school books such as Suite Scarlett and Truly Devious. My first experience with one of her young adult books was "Devilish," which, admittedly, wasn't her best. The story begins with Allison Concord, best friend to Jane Jarvis, our protagonist, throwing up out of nervousness. She has been anticipating her "Little"- freshman or sophomore students- for ages, and is afraid that she won’t get one, since Allison and Jane are seniors and the number of Littles numbers are fewer. Predictably, getting a Little requires some form of popularity and likeability. Allison values both, and this trait of hers spurs into motion a series of events that lead to her eventually getting possessed. (More on that later) Jane, on the other hand, cannot seem to care less. (Which is more expected given that senior students in most books typically ignore the lower-grade students.) Allison’s unusual obsession with this program is weird, but everything that drives her personality is too. Which is probably why when the freshman transfer student (because of course our villain has to be a transfer student nobody knows about) says she can make Allison’s wildest dreams of gaining popularity come true. Allison agrees, going so far as to sign away her soul. If a hundred other girls were put in Allison’s shoes, they would’ve burst out laughing. Or throwing up, since that seems to be established as the status quo.. Because, I mean, can we just take a moment to acknowledge what Allison has done? A new student who has zero friends expects you to trade your soul away, and Allison gives a very rational, very normal response: “Where’s the pen and where do I sign?” One of the glaring issues in this book is that we don’t understand why Jane and Allison’s friendship is worth fighting for. Jane is betrayed by Allison whose betrayal includes- but is not limited to- a secret relationship with Jane's ex, who Jane is decidedly not over (as evidenced by her hundreds of torn-apart letters). As a result, the motivation to root for Allison flies out the window very early on. That being said, there are some really impactful scenes in this book that stood out. Although we don’t get to see much of what Jane and Allison’s friendship used to be like, and Allison’s (selfish) motivations make her unlikeable to the readers, we are definitely made to sympathize with the protagonist (and thank god for that). Unlike us readers, she truly does love her best friend. So much so that it is hinted at that there may be something more between her and Allison, but I digress. A particularly moving scene is where Allison is having a panic attack after regretting the deal she has made with Lanalee, to the point that she runs to the bathroom with pills to take her own life. Jane follows her, and her desperate attempt to save her best friend is raw, truthful, an anguished reaction illustrated beautifully.This is where some type of magic occurs, and it is a shame that the story doesn’t shed too much light on this magical aspect. To clarify the fantasy aspect, there’s a system of spirits that search for easy victims. Then, they possess their bodies and sell their souls, which is a sentimental comparison of the ongoing fight for fame in this world today. Anyway, there's some organization where the spirits can level up in "ranks" depending on how many years of experience they have. Experience with what, you ask? Experience with entering a victim's body and forcing themselves to bleed to death on behalf of that body. Jane, as a character, intrigues me because her personality can be snappy, impatient, and arrogant, the cause of which is rooted in her intelligence. She describes herself as someone who can understand anything as long as she tries, from academics to the reason behind her best friend turning against her. However, this intelligence isn’t showcased in any way that contributes to the plot. Jane has perfect grades, yes, but in the book, in terms of street-smarts, it wasn’t outstandingly above average. After all, the wisest thing to do was to leave Allison alone and cut her losses. As for the other characters, most of them were static all throughout. Some appeared interesting, and one who had the potential to be compelling was Mr. Fields. At first, one gets the impression that he is just some creep who wants to help Jane for questionable reasons. The same can be said for Brother Frank, the school’s teacher, who is on the good side. However, as the story progresses and Mr. Field’s true identity is revealed, he plays almost no part in growing the supernatural origin story. Sister Charles had an interesting, dark backstory too, and after the horrific plot twist that she went through, one would expect that the story would explore her character more. However, the opportunity was completely wasted. And this is just one example of the many things that could’ve been unveiled or delved deeper into. On the other hand, I did not enjoy Jane’s relationship with Elton. Every time Elton faces a problem, he runs away from it. He didn't confront the issues when Allison needed help. Near the end of the book, it became faster in pace when Jane’s assignment from Lanalee, in order to be set free from their contract, is to get a kiss from Elton. This gave me immediate whiplash, not allowing me to fully immerse in the plot. There were so many ways the story could’ve resolved the issue of Jane getting out of the contract. Ways that would have given Jane more agency. The good thing that came out of this was that the readers could appreciate Jane’s adhesion to her moral code by not kissing her best friend’s new boyfriend. It shows her sincerity and made her much more likable. In typical Maureen Johnson manner, Jane is able to be set free from her contract without having to kiss Elton in a witty and unexpected way. Jane eventually does get over Elton after realizing he isn’t someone who sticks with her until the end, but a large impact of this discovery is less on character development than it is because of Owen, an immortal teenager who stole her heart. I wish that instead of so much time spent on these romances, we could have gotten Lanalee’s backstory. Our villain could have been fleshed out deeper than being a stereotypical psychopath with a knack for unhinged sarcasm. Moving on, even after Jane finds a loophole in Lanalee’s deal, Lanalee has one last trick up her sleeve. The ending had me quite confused. Owen, now Jane’s romantic interest, tells her, "You’re with us now." This means that Jane is now a part of the organization that stops such soul-possessing devils, but what exactly will she do in this organization? Cut people’s toes again (yes, that happens)? Also, won’t anybody notice in the future that Jane’s boyfriend is immortal? Overall, Johnson’s voice in every book she pens always stands out because the narrative is comedic and sassy and, most importantly, relatable. Cailey tinCailey Tin is an interview editor of Paper Crane Journal. She is an Asia-based staff writer and podcast co-host at The Incandescent Review, and her work has been published in Fairfield Scribes, Gypsophila zine, Alien Magazine, and more. She has work forthcoming in the Eunoia Review and Cathartic Lit. Visit her Instagram @itscaileynotkylie.

Caption: The Virgin Annunciate, Antonello da Messina, c. 1476. The Virgin is, here, come to the knowledge of her conception of Christ not by an angel but from the book before her, from the Word. The act of materially impossible conception, the birth of Christ, comes to be, comes to existence, only when it is written of, passing from the Virgin’s verbal annunciation to the written chronicle of the birth, passing from Word to Word — with the material being of the birth of Christ between these, with the fleshly and actual real, with the time of the phenomenon, being irrelevant, if not nonexistent. The Virgin hears the announcing angel, reads the text before her, and at once knows of the birth, at once births and foresees and remembers. It is written, and it is known and was and is at once. Thus the world is made in or by the Word; thus we are made and come to know ourselves as our gaze falls upon the Word; thus the Word is the initiating gaze of God, as the face or mask of God, which we reciprocate; thus we, as the Virgin, birth the Word and from our rotting flesh eternity comes forth, thus in dust and at the end eternity begins, the Word stands. What, in its creation and being, emergence and existence, movement and stasis, action and witness; what, in its creation of itself and of its subject; what, in its spontaneity and eternity; what, in its appearance, sudden or eternally postponed; what, in its beginning and end and timeless being; what, in the reality, in the world it creates; what, in its creation and its gaze upon itself, upon its creation and upon the world; what, in all these, in itself, is the Word? Treating the Word simultaneously to be the singular or particular element — though in itself a whole of wholes (syllables, morphemes, etc.) of parts or indivisible wholes (individual letters) — of language, of language as art (poetry) and to be the whole of language and of the poem, the word becomes a whole in itself (the particular word) and a whole existing or emerging as the apparent accumulation of wholes (the Word of particular words) — or the image, the indivisible reflection, of such an accumulation. We then approach the question of the Word as symbol, as mask behind which there is nothing; the question of the birth of the Word, whence it comes and whither; the question of the Word’s subject, that which the Word represents, mimics, becomes — the mask which the Word (itself a mask) wears; the question of the Word’s meaning, the subject which the Word itself creates, either initially or retrospectively; and the question of the Word as it is in the subjective, passive and absent gaze — the Word as it emerges and moves forth and stands motionless in its being, at last part of a greater indivisible image (a poetic image whole), reflected from the sum (the above accumulation) of words. The last question — of the Word as it is in our subjectivity, our absent gaze, as it is thus a perception or symbol of its objective self, a mask before a mask before nothingness or absence — presents to us the conclusion, or rather a notation which is stepping stone along a greater path, that the Word creates itself, demarcates itself its terms and limits and foundation for existence. This self-birth nevertheless is not preceded by this self-demarcation of the footing for this birth, but the latter process occurs simultaneously with the former — both thrusting the Word into absolute existence (absolute existence as object-existence that does not follow any movement of becoming, towards existence) — the Word, in its birth and foundation to hold its birth, being neither emergent nor moving but already existing. The Word does not emerge from out or within the present time, from out or within our gaze, as a phenomenon, but rather enters our gaze from without, stands across from us, in absolute and timeless being — and we, mute, wordless, take the Word — that come to us from outside our gaze and our subjectivity — for our own. The Word is neither emergent from nor existent within our gaze which is directed towards the present, our subjectivity, but comes to us and emerges from us as a timeless, abyssal, insuperable whole of itself. This is to say — as the ancients called poets prophets (poeta vates) — that the Word, if a timeless transcendent and descending whole, is the face God, a mask behind which is the presence of absence, a symbol which thrusts forth and stands unmoving in absolute existence, without a present or past or future. And as the Word descends and falls to come within our gaze, we scarcely raise our heads and already we see it in its wholeness and know it and birth it from our lips and pens as the fruit of our thought — a fallen, mortal, material fruit that was whole and eternal before its earthly conception. The resultant sum of words — brought into ink from the thrusting forth of this wholeness, this poetic force in thought — similarly births itself and builds the foundation to hold its birth simultaneously. And, at last, this divisible sum of words creates through reflection an indivisible image (the poetic image whole) which creates, inhabits and transcends each word and part; this image, then, is the Word, the mask before the mask, the face of God in its absolute, unconquerable, unmoving presence and existence without birth or death. The space across which this poetic image whole is reflected is an empty space, the material world, the world of thought, the world and being behind the subjective gaze. The Word — as we see it and take it and cast it with our rotting hands onto the rotting ground — is eternity surrogated by mortality, gold found amidst but not formed from dust. It is our tragedy, of our blindness, that our gaze sees our end and nothing beyond it. As it is a presence, the Word is the face of God, a mask which looks at us and we at it, which speaks to us and we write — and we, poets, fall into the earth, kissed and thrown forth by the divinity. We weep and trace an eternity in the dust, we weep and from our rot sing our tragedy, we weep and birth the divinity and end after the birth — we, mute surrogates, passive hordes — seeing, knowing, weeping and without words. Nickolas vaccaroNickolas is a columnist for the Paper Crane.

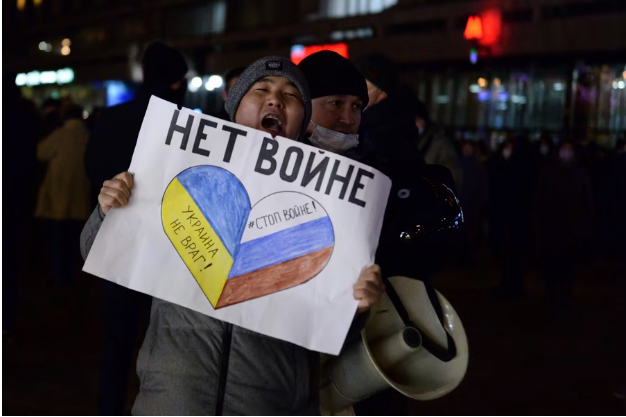

A demonstrator in Moscow being detained by police. The poster reads “No to war” and “Ukraine is not our enemy.” Associated Press. The question of national identity, and the questions of national sovereignty and territorial integrity which arise from the question of national identity, all of which are central to the Russo-Ukrainian War, must be defined categorically, addressed and resolved universally, if this war, and the historical conflict of which it is born, is to end at last — if at last life, the human right to live, is placed above everything else, above all ideas and philosophies and politics, if at last the guiltless masses cease to bleed for the ideas of the fanatical few. Language — as it is the expression of a people, their distinct political and cultural voice that emerges out of historical conflict, settlement and political struggle — prescribes the individual to a people sharing the language and, consequently, to the history, artistic and literary expression and political struggle of that people. These facets of society — historical and political consciousness, artistic and intellectual expression — as much as they exist within language and are born from language, create for the people of that language a collective understanding of self, of shared history and present-day politics — a collective world-gaze which, as distinct from those of other societies, drives a distinct expression through art and politics. This drive for expression (and thus for existence), as it is directed by collective history, creates a collective people’s culture and concept of nationhood or national identity. Being born of a people collected together through shared historical and political experience, with a shared world-gaze, national identity has its original root in language. After language, a people, then a collective consciousness, then a world-gaze, then a culture and politics, then a society and national identity come to be. A nation, then, comes into being after all the aforementioned as a political, practical, differentiation of that people and history and culture, of that society and language, from all others. A political state emerges out of that people, a society forms, geographical borders are defined — and so a nation, as a practical institution for the preservation and protection of a people and history and culture and the language that binds and births all these, comes to be. Thus, a people’s national identity, and the language in which it exists, precede and transcend the nation which is a political and purely practical institution that holds within it a people and their identity and language but can in no sense be equated to these or conceived to inform these. Russia — as Nazi Germany in the last century and all fascistic and fanatical societies that place the realization of a political or historical-religious mystical vision before life and the individual’s right to live — has premised its aggression in Ukraine and violation of the practical structure of nation (and national borders) on the suggested Russian national identity of inhabitants of eastern Ukraine, a claim deriving from the Russian language usage of those inhabitants. Russia would annex Ukrainian national territory and establish a Russian nation, in the practical structure of a nation, after violating Ukraine’s nation structure; denying a people’s and the individual’s foremost right to live which precedes any notion of national identity, history or language; and thus rejecting the necessity of a nation as a practical structure functioning, in the first place, to preserve a people, to protect human life. Russia’s hypocrisy in first violating the (Ukrainian) nation structure, dismissing the foremost value of human life, only to erect a Russian nation structure over mass graves and razed cities — neither to preserve a people nor to protect human life, but first and foremost to establish a new and false national identity — must be denounced, socially and politically, and prosecuted, legally, in the strongest terms and with greatest urgency. For, as any fascistic war, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, reverses the purpose of the political and practical nation structure from firstly preserving a people and thus human life to firstly preserving a national identity, culture, history and language. This reversed nation structure is false — for neither can national identity exist without human life nor should it, as any political ideology or philosophy, be valued before human life or be built on its oppression and sacrifice. We, living not a hundred years since the Holocaust, since the second World War, since the Bosnian and Rwandan genocides — we, inheritors of the last century’s evil, our forefathers’ evil, began our century’s first war in Europe and have turned deaf to the historical cry of all those millions oppressed and persecuted and slaughtered. And we commit the same sin, carry into our century the same evil: to value ideas and ideology before life, history and politics before life, national identity before life, land before life; to oppress, conquer and triumph; to deny, again and again, that others have the right to live, the right to life, that they are human. The war must end, but only with the victory of the nation over national identity, life over ideology, Ukraine over Russia. And as language, as a people and their collective identity and distinct world-gaze, as national identity, transcend the practical nation structure, they must not remain passive to their nation’s bleeding, to its strife for survival — for the nation protects a people, preserves language and history and identity. And without the nation, without just politics and incorruptible law, without principle and courage, we, the people of the world, against evil, in our struggle to life, for all our visions and histories and philosophies, are nothing. nickolas vaccaroNickolas is a columnist for the Paper Crane.

Mr Smith Goes to Washington centers on the efforts of an individual senator against a legislature nearly totally corrupted by a political machine (controlling both public opinion and the government’s private dealings), greed for political and economic gain, and fear of retribution and political ruin for anything less than total allegiance to the political machine’s agenda. Corruption being thus entrenched and the function of government being thus perverted to serve only its members’ personal gain, Mr Smith (in believing politics to be honest, the Senate virtuous and the endurance of the founding principles of American democracy in modern politics) represents the outsider’s, the idealized view of government. The absurdity of Mr Smith’s ignorance is a counterpoint to the absurdity of the total Senate’s corruption, and, while both are improbable, Mr Smith’s characterization is necessary within the satire that is Mr Smith Goes to Washington. Although Mr Smith’s character, his naiveté and boyish reverence for the American ideal are sentimental and improbable, analogs to his qualities of outsider and disrupter of the status quo (and to his popularity for these qualities) may be drawn from the popularity of the outsider and disrupter in modern American politics; this popularity, unlike that of Mr Smith, stems from public cynicism or apathy, not, as in the film, from idealism. The film portrays corruption as the norm in state and federal government and personal gain as the aim of government. In this, the film exaggerates the profusion of government corruption, and to this exaggeration the opposite must likewise be an exaggeration: Mr Smith, in contrast to those in power who view power and government as a means for profit, believes that American democracy is unconditionally just, its principles immovable, its founders infallible. Mr Smith, therefore, does not recognize the necessary imperfection, conflict and confused but democratic progress that is government. In this way, Mr Smith’s characterization is improbable for a senator, although necessary to the plot. Arriving in Washington with little more than knowledge of American history and abstract sentiments on the virtue of American government, without any knowledge of the practicality of government nor the sensationalism of the media nor the extensive influence of Taylor nor the cynicism of senators, Mr Smith’s effort to pass legislation creating a national boy’s camp becomes a struggle to defend himself against slander, against Paine’s accusation of fraudulence, to prove himself honest and his slanderers fraudulent. Reciting the Declaration of Independence and Lincoln’s Gettysburg address, Mr Smith struggles to remake the Senate into the honest, virtuous body he believed it was; to accomplish this he must overcome Taylor’s influence and the senators’ greed and fear — thus disrupting the corrupt status quo. In this, Smith’s characterization as disruptor is necessary to the plot, believable and applicable to modern politics. Modern American politics is in part defined by the public’s belief, however unfounded, in the corruption of government. This belief in institutional and, increasingly from the Republican party, electoral corruption attracts cynical or apathetic voters to populist, seemingly outsider candidates (as Donald Trump) who are characterized as Mr Smiths: honest candidates seeking power only to remake government, removed from the practicality and intrigue and thus the alleged corruption of the status quo. Beliefs in the entrenched corruption of government are unjustified and threaten to remake a just democracy into a tyrannous rule of the majority; populist candidates, like Donald Trump, who claim to fight corruption sooner are themselves corrupt, self-serving and undemocratic. Thus, the idealized, virtuous, disruptive image of the political outsider that is Mr Smith is applicable to modern politics sooner as a facade to self-interest, disruption of a democratic status quo, and the chaos of authoritarianism than a necessary reality. Mr Smith’s knowledge of American history, reverence for democracy and American government must be met by the modern politician with a critical and constructive perspective and comprehensive knowledge of the practicality of government. The importance of Mr Smith Goes to Washington is its exaggerated, satirical quality which portrays the potential for the corruption of any government, even of American democracy, if the politician fails to balance idealism and skepticism, traditionalism and innovation; if greed is followed before duty; if power becomes its own end. The film at once cautions against cynicism and encourages skepticism and nuanced understanding of politics. In a time of increased polarization, misinformation, media bias and intolerance of disagreeing views, the film portrays the potential for any government to corrupt, any democracy to cease to believe in itself and in the power of one individual against injustice. This portrayal of what may be if we surrender our individuality, our healthy skepticism to the apathy and discontent by which authoritarianism comes to power, is ever more relevant. The improbable character of Mr Smith is, then, a symbol of the might of the individual, the urgency for principled government and faith in democracy, the importance of moderation, the necessity for tradition and improvement — for no institution or individual is without flaw. nickolas vaccaroNickolas is a columnist for the Paper Crane.

1 Caption: Tietê bus terminal, São Paulo, Brazil, 1996, Sebastião Salgado To me this photograph embodies the relation of language and art to reality. The photograph captures the physical and intellectual aspects of freedom — as they contradict and contend with each other. The people — grasping the gate, as though beginning to climb it — look in the same direction as the woman in the foreground. Physical separation, the absence of physical freedom, is meaningless in the photograph’s moment: the people and the woman are all there where they look. And yet the people and the woman as we see them exist only in the photograph; they are not real; they look somewhere off, somewhere and nowhere. We presume that the people are captive and the woman is free; but they all have time neither for thought nor language; they can only exist; they are made captive in their existence by the photograph, the work of art. This is the contradiction of art. This is art’s struggle for truth. In looking at the photograph we look at the minds, not the bodies, of the people and the woman. The people and the woman together create a reality; that reality is not physical. That reality, the photograph, is an abstraction, an empty metaphor without meaning, a metaphor that precedes meaning. This abstraction is the function of poetry (poetry in the linguistic or visual or musical art); this poetic metaphor treats human beings as minds (intelligences, as Ezra Pound had it), and through abstraction, through metaphor poetry makes its subject ubiquitous. The people behind the gate and the woman in front of it, as a poem’s words and lines, morph into a singular impression that precedes meaning, a singular metaphor and abstraction that precede meaning (not unlike Keats’s negative capability). Abstraction and metaphor, then, are the functions of poetry. The captives and the woman are all captive in themselves; they, to us, are not their real selves but symbols, abstractions of themselves; they are a language, as language is in poetry, of art. To us, they are symbols of an eternity, minds, the only divinities — only for a moment, only in the photograph, only as art, they are free. 2 Now we feel most acutely — as all peoples in all times likely have — the danger of language. It is the danger of deceit, ignorance and blind belief. Language used only to communicate, concerned only with its effect and not its construction, is at once essential for everyday interaction and a political weapon. Language — an idea and a practice inseparable from our human identity, individual and shared, and fundamental to our need for expression — is, however, entirely unethical: it is a tool which anyone, irrespective of ideology or justice of intent, can use to great effect. Language, then, is a result, a product of thought and of self — released into the world to contend with others’ thoughts and selves, others’ language, for acceptance and effect. Language, such as political rhetoric, has the immense and dangerous power to create worlds — realities that agree with one or another political ideology; that draw a border around one or another community; that drown out through zeal and fear and rage opposition and argument; that have no room for one or another idea or people or, most dangerously, for actual reality. Here lies the danger — in language that, by creating realities, rejects actual reality. Antisemitism, war justified with simplified and selected history, the denial of climate change, nationalism, censorship, repression — all these, real-world manifestations of private ideology (private belief, prejudice etc.), inhabit our world through language. And in order to exist, to continuously reinvent and reproduce, the language of ideology — of prejudice and persecution, nationalism and political zealotry — must be deafening: it must not give voice to disagreement or fact; it must not be rigorous or profound; it must be accessible and exciting. Prejudice, and the language by which it exists, cannot be informed by reality — for to build ideology on the basis of fact, to admit error, to value common good over ambition, is inconvenient, counter to ambition, practically impossible for the tyrant or conquerer or bigot. For their identity to survive, for them to survive, for them to hold onto power, they must not lose their hunger for profit, they must not waver even in the face of their deceit, they must not loosen their grasp on the reins holding a nation by its throat — pulling it back and tugging it along. The tyrant’s language must not answer reality but create it. Misinformation — finding faster wings, becoming more subtle and total with every year of technological innovation and expansion — is the essential struggle of our generation. And yet, turning to history, braving to look at it fully, objectively, braving to remember genocide, conquest, oppression and the ideologies from which these were born and the language with which these existed — considering these, the struggles of the present, much like deceit itself, seem nothing more than reinventions of the past, unknown only at the face and ignored in passing. Literature, particularly poetry, is an answer to the weaponization of language. Poetry is concerned not only with the effect of language but with its construction, recording reality and not creating it, contradicting itself because the world contradicts itself, stumbling toward truth — the truth of human existence and emotion and identity and ideology. Truth, unlike deceit, has no need to speak, only to exist. It is silent, there for all who look. Poetry is the struggle for truth, the struggle that is truth. It is a contention between feeling and fact, speech and silence, presence and absence, image and sound, sight and blindness, message and form. It is essentially contradictory. Poetry, literature, art are someone’s — the artist’s and the world’s — quiet stumbling steps toward truth — or, if not that, then whatever it is we are, whatever it is the world is: humanity, emotion, ideology, identity, sickness, folly, noise, silence, presence, absence, something, nothing — all vain hope to find something in nothing, all optimism, all a lie. NICKOLAS VACCARONickolas is a columnist for the Paper Crane.

|

Details

Archives

February 2024

CategoriesWould you like to publish a guest column? Insert your email and we will contact you.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed